Earlier this week, during a press conference at Mar-a-Lago, President-elect Donald Trump announced that Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a long-time anti-vaccine activist and current nominee for head of the Department of Health and Human Services, will be tasked with investigating high rates of autism. When pressed by reporters, Trump refused to state definitively that autism is not caused by vaccines.

This isn’t the first time Trump has promoted fear around vaccines and autism. In fact, he’s been spewing this slop for more than a decade. In 2014, for example, he tweeted in classic Trumpian cadence that:

“Healthy young child goes to doctor, gets pumped with massive shot of many vaccines, doesn't feel good and changes - AUTISM. Many such cases!”

The reality, of course, is that vaccines do not cause autism—a fact we’ve known since long before Trump became a political player. The first paper positing this link was published in The Lancet in 1998 by British gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield. Yet, after more than a decade of follow-up research, other scholars were unable to replicate Wakefield’s findings, which led to a retraction from The Lancet and an investigation by the UK’s General Medical Council, which found Wakefield to have acted “dishonestly and irresponsibly” in conducting his research and with “callous disregard” in publishing the results.

So, why won’t this lie die?

The answer may have less to do with vaccines themselves than with the fact that, in the US, we treat mothers as both our scapegoat and our social safety net.

To understand what I mean here, we have to go back to the 1940s, when doctors first began diagnosing autism as a childhood disorder. Psychologists at the time worked mostly from a Freudian perspective, which interpreted mental disorders as a function of childhood traumas, and which tended to trace childhood traumas back to “bad moms.”

Building on these ideas, psychologist Bruno Bettelheim blamed autism on what he called “refrigerator mothers,” or mothers who were too emotionally “cold” to their child. The refrigerator mother theory quickly became the leading explanation for autism, and it was used not only to sell books promising to teach “good” mothering, but also to justify separating autistic children from their families, placing them in residential facilities, and stripping their mothers of parental rights.

Essentially, mothers of children diagnosed with autism were treated as scapegoats—blamed for their children’s conditions and punished for being “bad moms.” Mothers themselves weren’t satisfied with Bettelheim’s explanation. Yet, they had little power to resist medical experts’ judgments. And even after some experts began to question the refrigerator mother theory in the 1960s and 70s, mothers of children with autism still struggled to overcome lingering public scrutiny and stereotypes.

That is, until Wakefield came along. Wakefield’s vaccine theory gave mothers a new scapegoat to blame for their children’s autism. And so, as sociologist Jennifer Reich documents in her book, Calling the Shots, they became some of the most vocal proponents of Wakefield’s claims.

Decades later, and despite Wakefield’s debunking, some mothers still find solace in the absolution his theory provides. Take, for example, a mom I’ll call Tara—one of the women I interviewed for my new book, Holding It Together: How Women Became America’s Safety Net. As a toddler, Tara’s daughter Reagan experienced a sudden shift in temperament not long after getting her routine vaccines. As Tara explained:

“We are pretty sure that vaccines caused my daughter to regress. She was perfectly fine. She was meeting all of her milestones at a year and a half old, and one day it was just all gone, and she started having meltdowns. She started not liking people. She doesn’t talk.”

Reagan’s pediatrician made a referral for testing for autism, but the waitlist for appointments was a year long. Private testing might have been faster, but Tara couldn’t afford to pay, because she was pregnant again and had experienced complications that forced her to leave her factory job. In the meantime, Reagan’s condition got increasingly difficult to manage, leading Tara to decide not to go back to the workforce, even after Reagan’s younger brother was born. As Tara explained, “She uses me as her security, so her own dad doesn’t know how to help her calm down from a meltdown.” In the face of that stress, vaccines gave Tara a target for the grief and the anger she felt on the days that were especially hard. Tara also opted not to immunize her son or give Reagan or her older daughter any further vaccines. As she explained: “I’m afraid that if I get vaccines for the other kids that it’s going to happen again.”

Over time, fears like Tara’s have become widespread in the US. A recent survey conducted by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center found that 24 percent of the 1,500 American adults they surveyed believe that it’s inaccurate to say there’s no link between autism and vaccines. And that same survey found that only 43 percent of American adults think the vaccine explanation for autism is definitely false.

Those beliefs are in part the product of fearmongering—efforts to sow doubt in the safety of vaccines, often by bad-faith actors looking to profit by selling parents some supposedly “safer” solution instead. At the same time, the success of those fearmongering efforts has, ironically, been helped along by the success of vaccines themselves. Today—and because of vaccines’ effectiveness—once-common childhood diseases like measles are now extremely rare in the US. So, the serious threats posed by those diseases no longer loom as large in parents’ minds, making the risk of autism seem, by comparison, like a much bigger threat.

To see that thinking in action, consider another mom, who I’ll call Erin, and who told me about her struggle to decide whether to vaccinate her infant son.

“On one hand, I don’t want to risk him getting exposed to diseases that could hurt him, but then on the other hand, autism is scary, you know? Each kid responds differently, and there are kids that have problems after their vaccinations.”

For Erin, those fears were compounded by what she called her “family history” of autism, which she worried would “make vaccine damage more likely” for her son. Given those fears, Erin ultimately opted to skip the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine—the one that Wakefield’s study linked to autism—and the rest she opted to delay and space so her son never got more than one at a time.

So, why do moms like Erin fear autism?

It’s partly because, even though we no longer talk about refrigerator mothers, our culture of mother-blame never really went away. In the US, and to keep taxes low for billionaires and big corporations, we’ve made healthcare a private good rather than a public one. That model leaves us sicker, sadder, and more stressed than we might otherwise be. But the profiteers who benefit have managed to maintain the status quo by persuading Americans that we could be healthier if we just made “better choices,” and that sick people are only worthy of sympathy and support if they’ve tried to stay in good health and in good shape. When it comes to kids, however, we recognize that they’re too young to make “healthy” choices without prompting. So, we just shift the moral judgment to parents—and usually to mothers—who are treated as the prime suspects when kids struggle with physical, mental, behavioral, or academic problems.

On top of that mother-blame, there’s also the burden of care. In the US, and because of our privatized healthcare model, the work and the cost of dealing with illness falls primarily to individuals, and thus to parents (and usually mothers) in the case of families with kids. As a result, even a minor illness—like a cold that keeps a child home from school for a day or two—can take a heavy toll on mothers. Some may be unable to take time off from paid work, while others may have to take unpaid leave or do double-duty, working remotely while caring for their child at home. For mothers whose children suffer from serious or chronic conditions, that toll increases exponentially, to the point where it often becomes impossible to care for their children while sustaining a full-time career.

Against this backdrop of mother-blame and mother-burden, it’s not surprising to see mothers fear the prospect of their children being disabled or seriously ill. Erin, for example, had seen family members struggle with the challenges of raising a child with autism—challenges that can include long wait times and high out-of-pocket costs for diagnoses and treatments, fights with schools over appropriate accommodations, and emotional meltdowns if their children’s needs and routines aren’t met. Erin also worried that if her son did develop autism, she wouldn’t be able to afford the care he might need as result. She told me that she and her husband were still struggling to pay off the thousands of dollars in medical debt they owed after giving birth, and that they were also “going broke for insurance,” trying to pay their healthcare premiums and out-of-pocket costs every month.

Fortunately, there’s another way forward that doesn’t throw mothers (or kids with autism) under the bus. That solution is to decouple health from morality, treat all people as deserving of dignity, and take collective responsibility for care.

Of course, all of that is easier said than done. But, a good place to start would be to make healthcare a public good instead of a private one. A public healthcare model might not immediately change people’s minds about vaccines and autism—confirmation bias makes misinformation too sticky for that. But, that public healthcare model could reduce the fear that drives mothers to look to vaccines as scapegoats. Because, in the context of a stronger social safety net, mothers could trust that if (and more likely when) something goes wrong with their children’s health, the blame and the burden wouldn’t just fall to them. ●

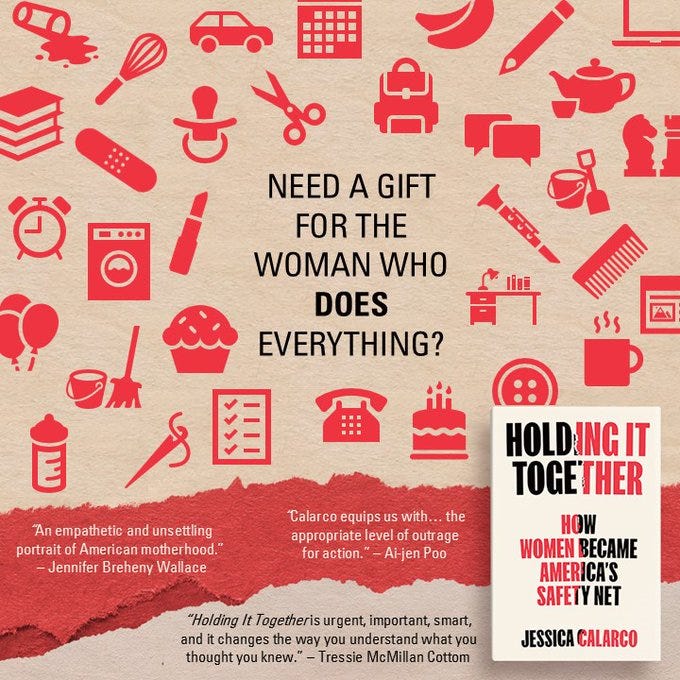

Holding It Together for the Holidays

We like to think of the holidays as a time of joy and celebration, but for many, they’re a time of frustration and stress. Some families try to manage the stress with a divide-and-conquer approach—my husband does the decorating and the cards and the travel planning, while I do the baking and the teacher gifts and the crafts with the kids. Too often, though, the bulk of that stress falls to women, who are usually tasked with creating the “holiday magic” for everyone else, and getting only a “#1 Mom/Grandma/Aunt/Sister/Daughter” mug as thanks in return.

To that end, if you’re looking for a last-minute gift for a woman who does everything, Holding It Together is a gift of recognition and a gift of ungaslighting. It’ll show her that if she's burned out, it's not because she didn't lean in, wash her face, or let that shit go; it's because billionaires and their cronies maintain the illusion of a DIY society by forcing her to work overtime and underpaid creating the safety net on which everyone else relies.

And maybe, if you’re feeling particularly cheeky this holiday season, you could also gift a copy to the men who ought to be doing more to help the women who are burned out trying to do it all.